The Commodification of Higher Education

Colleges and universities have become a marketplace that treats student applicants like consumers. Why?

This is the third story in a three-part series looking at elite-college admissions. Read the first story here and the second one here.

When the U.S. News & World Report rankings were first published in 1983, they equipped students with what had previously seemed to be top-secret information about colleges and universities. They highlighted the practical role of higher education—something in which students (and their families) were investing to improve their lives. “College is expensive,” said Robert Morse, the chief data strategist for U.S. News, via email. “U.S. News’s mission is to arm students with good data, enabling them to sift through lots of complicated information when deciding which school is the right fit for them.” The rankings allow students to compare schools in an (arguably) apples-to-apples way—allowing students to, according to Morse, “navigate the complex process of choosing the best school for them” and creating “a national move towards greater transparency in the education industry.”

Many educators see the rankings in an entirely different way.

They’re “highly pernicious,” said Michael Roth, the president of Wesleyan University. “I think they’ve had a really deleterious effect on higher education as [colleges and universities] try to meet requirements that may not be in the best educational interest of their students.” The Education Conservancy founder Lloyd Thacker thinks the rankings have had such a disastrous impact on higher education that he edited an entire book—College Unranked—aimed at reminding “readers that college choice and admission are a matter of fit, not of winning a prize, and that many colleges are ‘good’ in different ways.” Critics like Roth and Thacker say the rankings contribute to the admissions frenzy, giving the impression that the most desirable schools—irrespective of the applicant and his or her specific interests and needs—are the ones at the top of the list, the ones that are harder to get into. “They accentuate the race toward the wealthiest schools,” said Roth.

Few would argue that the rankings have helped shape a world in which students are seen as consumers, and colleges and universities as commodities. The rankings are a key reason the higher-education landscape today operates like a marketplace in which institutions compete to convince the best students to buy their product. Still, as The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson once argued, “college rankings aren’t the monster here. They’re the gnats on the back of a monster.”

That monster, as I’ve outlined in the first two installments of this series, is deeply embedded in history. The path higher education took to becoming the commercial industry it is today—a phenomenon that has severely warped the experiences of applicants to the country’s most selective schools—goes back several decades.

In 1979, Edward Fiske, the editor of the Fiske Guide to Colleges and a former New York Times education editor, wrote an article for The Atlantic titled “The Marketing of Colleges.” Reading the story leaves an unsettling feeling, largely because it was warning of a troubling trend—higher education’s “shift from a seller’s to a buyer’s market”—that has since played out in even more troubling ways than Fiske predicted.

This was pre-U.S. News and pre-Reagan; post-GI Bill and post-Common App. Access to higher education had expanded dramatically in previous decades, but high-school graduating classes had started to shrink. Colleges, particularly small, lesser-known ones, saw their revenues sinking; some were on the brink of shutting down. Desperate to enroll enough students to balance their budgets, according to Fiske, some colleges and universities started “turning to desperate new promotional techniques, such as handing out Frisbees on the beaches of Fort Lauderdale.” Others started recruiting international students. “Still others are turning to the business world for the techniques to keep themselves among the survivors of the academic squeeze to come,” Fiske wrote, “and a whole industry of admen, headhunters, direct mail experts, and marketers has popped up ready to meet their needs.”

The number of high-school graduates continued to shrink through the mid-1990s, until it started to rebound. It’s now at an all-time high. But despite that turnaround, the practices highlighted by Fiske haven’t gone away. Today, colleges promote themselves in TV commercials and with swag like slinky notepads and headbands. (Seriously, colleges think students love headbands.) They educate increasing numbers of international students; last school year, 1 million of them were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities, up 10 percent from the previous year. And they rely on a booming cottage industry of business-minded consultants—the exact kinds of professionals Fiske described—to help them with their enrollment and recruitment needs.

And it’s obvious, even to many of the teenagers currently immersed in the admissions process. “As someone who’s interested in [majoring in] business, something that’s really fascinated me is how schools market themselves,” said Sarah Ford, a senior at Milton Academy, an elite New England boarding school. “How their tour guides act, how their information sessions work, whether they use visuals or not, whether they cater to the parents or to the student.”

At the country’s most elite schools, these tactics are rarely last-ditch attempts to sustain student numbers and balance budgets. Rather, critics say they’re symptomatic of these colleges’ efforts to get as many students as possible to apply—and to enrolling what they determine to be the highest-quality applicants—in large part because of the pressure to fare well in the rankings and outshine their competitors. The larger the applicant pool is in relation to the student body, the more selective the school appears in those rankings. This elite-college marketplace, according to observers, helps explain why the admissions experience has become so intense.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, a series of federal higher-education cutbacks prompted colleges and universities to rethink their financial-aid policies. Colleges started to treat admissions and financial aid as intertwined rather than independent functions. A 2014 National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC) survey of admissions-office employees found that 73 percent of respondents at the most senior level were responsible for financial-aid operations. “Conversations pertaining to admission and enrollment targets, retention, financial aid, tuition setting and annual budgets take place in the same room,” said Greg Roberts, the dean of admissions at the University of Virginia, in the NACAC report.

The role of financial aid also evolved. Since the GI Bill and the enactment of the Higher Education Act, financial aid had been thought of as a tool to improve access and affordability. But new economic realities and competition for top-tier students forced postsecondary institutions to redefine its use. “Financial aid used to be a charitable act—just given to needy kids, kids who needed it the most,” The Education Conservancy’s Thacker said. “Now, we said, ‘We can use financial aid to serve strategic institutional interests, such as improving our rank, our status, and our prestige.”

This helps explain the dramatic rise in colleges’ merit-aid offerings—financial assistance for students independent of need—starting in the ‘90s. “Colleges see merit aid as an investment in institutional quality,” says a 2008 report by the Institute for College Access & Success. The report cites data showing that between the 1995 and 2003 school years, merit aid rose from $668 million to $2.1 billion for public four-year institutions and from $1.6 billion to $4.6 billion for private four-year institutions—largely limiting lower-income students’ access to higher education. The report’s authors, Matthew Reed and Robert Shireman, attribute the skyrocketing spending on merit aid to what they describe as “the bidding wars”: “Since top students are in high demand, colleges may have to bid against each other, raising the aid offered these students to well beyond their financial need.”

In 2003, 30 percent of institutional merit aid went to students with family incomes in the top quartile—including 21 percent of need-based aid. I can attest to the effectiveness of this approach: I was the recipient of a full-ride merit-aid scholarship to Boston University—and it was, in fact, the precise reason I chose to attend the school over a more “prestigious” institution.

The temptation to dole out more merit aid traces back to the rankings, which incentivize colleges to try and enroll top-notch applicants—applicants who without the financial inducement would otherwise opt for another school. This, again, is why educators are so skeptical of the rankings. Some even accuse U.S. News of corrupting the system.

Michele Tolela Myers, the former president of Sarah Lawrence who once analogized participating in the rankings to a game of roulette, has alleged that the publication opted to use flawed, publicly available test-score data to grade Sarah Lawrence because the liberal-arts school had decided not to use SAT and ACT scores in admissions decisions. (It’s since made the scores’ submission optional.) Under Myers’s leadership, Sarah Lawrence eventually dropped out of the rankings absent a compromise on how to deal with test data; it’s since rejoined. As a Washington Post article announcing the college’s return to the rankings noted, “This says something about how college leaders view the rankings they love to hate.”

U.S. News’s Morse denied the criticisms, describing many of them as myths. Schools don’t get a better ranking just by rejecting more students or building fancy gyms. In fact, he noted, “people are surprised to learn that the majority of students researching colleges on usnews.com are looking at schools outside the top 10—our rankings and information introduce students to the wide variety of schools out there.” He flatly rejected the notion that the publication “made up” a number in response to Sarah Lawrence’s decision not to use test scores. For a test-optional school where fewer than 75 percent of students submit test scores, U.S. News discounts the school’s average SAT and ACT scores in the methodology by 15 percent because it estimates that going test-optional would generally lower the average scores by that percentage.* “The reduced weight given in such test-optional cases is about keeping a balance in the methodology, assuring that U.S. News is ranking all schools in the most fair, comparative way possible.”

But resistance to the rankings has snowballed. “[Colleges and universities] ought to simply refuse to cooperate with these ranking services—have enough confidence in their own ability, prestige, etc, not to try to be influenced by a magazine that essentially wants to sell copy,” said Jonathan Cole, a professor and former provost at Columbia University. Cole is part of a growing movement within the higher-education world aimed at reducing the rankings’ clout. In fact, in 2007, Thacker convinced 60 college presidents to sign a letter declaring the rankings “misleading” and to vow not to participate in the portion of the U.S. News survey that asks presidents to rate each other’s institutions.

U.S. News’s influence over the higher-education market isn’t likely to lessen anytime soon. In 2015, roughly 70 percent of U.S. freshmen said reputation was “very important” when it came to selecting a college—the highest level ever, according to a survey that’s been conducted among students nationwide by UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute since 1967. As Thacker put it: “The signals that kids are hearing are: You gotta go to the one best school; the one best school is the one that’s hardest to get into; and how do I know what it is? It’s the one that’s most highly ranked.”

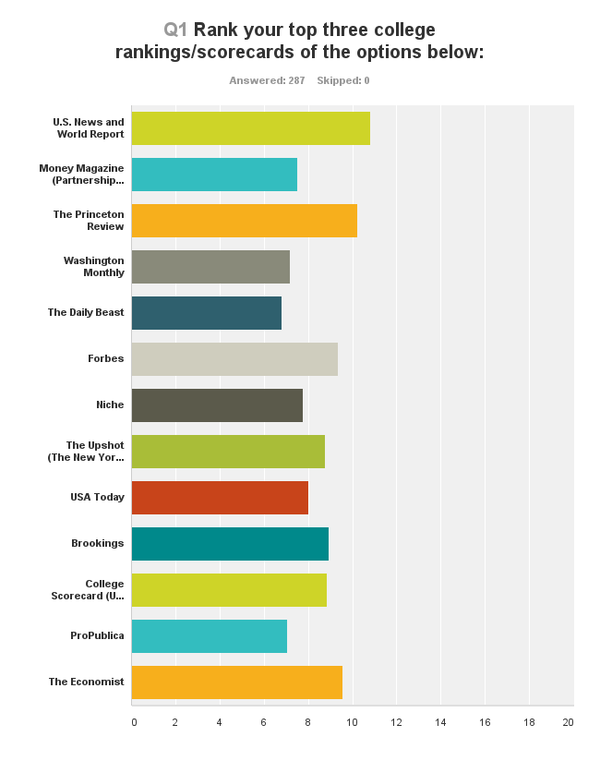

And when The Atlantic recently asked readers to rank the rankings, the winner—both surprisingly and unsurprisingly—was U.S. News. Other popular options were the rankings put out by The Princeton Review and The Economist.

Meanwhile, despite the withdrawal of many colleges away from standardized-test scores, administrators still generally seem to place a premium on them when it comes to admissions. According to a 2011 survey of college admissions directors, SAT scores are as important a factor in admission as grades.

Things are starting to change. Alternative rankings—such as those produced by the Washington Monthly and The New York Times’s Upshot—have emerged with the intention of focusing on things like access and social impact, placing significant emphasis on the number of students with Pell grants. They’ve effectively challenged the clout of The U.S. News’s algorithm and raised awareness about the importance of assessing more than just academic caliber.

And a coalition of colleges has recently banded together to produce a new type of application designed to equip students—particularly those who aren’t familiar with the admissions process—with the information they need early on when applying. Known as the Coalition for Access, Affordability, and Success, the new application system, as Laura McKenna wrote for The Atlantic, “is equipped with online tools designed to empower those students, in part by helping them find well-endowed colleges and encouraging them to hone their qualifications and admissions savvy throughout high school. This will set it apart from the Common Application, its most widely used counterpart, and protect students in case that system malfunctions—as it did in 2013.”

But this effort, too, has its critics. Jon Reider, the college counselor at San Francisco University High School, said it will further confuse those who are already confused and further stress out those who are already stressed out. “It’s going to make things twice as complicated,” he said.

And as for the movement away from admissions tests? Fewer and fewer colleges may be requiring applicants to submit scores, but that doesn’t mean their presence is waning. According to a recent Education Week analysis, high-school testing is tilting heavily toward those very exams: Twenty-one states now require students to take the SAT or ACT, and a dozen use one of the exams as part of their official, federally mandated accountability reports on high-school students. As the Harvard Law professor Lani Guinier, a staunch critic of elite-college admissions, wrote in her book, The Tyranny of Meritocracy: “This is testocracy in action.”

* This article originally mischaracterized the process by which U.S. News & World Report handles scores of test-optional schools. We regret the error.