To get to the Panoptic Studio at Carnegie Mellon University, you take an elevator down four flights to a dingy sub-basement. Inside room B510, a series of metal cross beams enclose a massive, otherworldly structure: a geodesic dome. Each of the wooden dome’s hexagonal panels is covered with a tangle of wires, cameras, and connectors, and a steady thrum emanates from the rows of computers that surround the hulking structure. At the bottom of the dome, a single panel is missing and bright light streams out, making it difficult to see what’s inside. It looks like a portal to another dimension. “People, when they come in here, they often ask us what this thing is,” says Tomas Simon, research assistant in the lab, with a joking grin. “We tell them a time machine, and usually they believe us.”

Step inside the portal and everything is white, calm, silent: this is where researchers are helping craft the future of virtual reality. I speak out loud, and my voice echoes around the empty space. In place of the clutter on the outside, each panel is unadorned, save for a series of small black spots: cameras recording your every move. There are 480 VGA cameras and 30 HD cameras, as well as 10 RGB-D depth sensors borrowed from Xbox gaming consoles. The massive collection of recording apparatus is synced together, and its collective output is combined into a single, digital file. One minute of recording amounts to 600GB of data.

The hundreds of cameras record people talking, bartering, and playing games. Imagine the motion-capture systems used by Hollywood filmmakers, but on steroids. The footage it records captures a stunningly accurate three-dimensional representation of people’s bodies in motion, from the bend in an elbow to a wrinkle in your brow. The lab is trying to map the language of our bodies, the signals and social cues we send one another with our hands, posture, and gaze. It is building a database that aims to decipher the constant, unspoken communication we all use without thinking, what the early 20th century anthropologist Edward Sapir once called an "elaborate code that is written nowhere, known to no one, and understood by all."

The original goal of the Panoptic Studio was to use this understanding of body language to improve the way robots relate to human beings, to make them more natural partners at work or in play. But the research being done here has recently found another purpose. What works for making robots more lifelike and social could also be applied to virtual characters. That’s why this basement lab caught the attention of one of the biggest players in virtual reality: Facebook. In April 2015, the Silicon Valley giant hired Yaser Sheikh, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon and director of the Panoptic Studio, to assist in research to improve social interaction in VR.

"There is nothing people are more keenly aware of than other people."

For Facebook, virtual reality represents the next great computing platform and the ultimate evolution of Zuckerberg’s social network. Our communication has evolved from text to photos to video to live video and virtual reality is the obvious next step. "We all know where we want to improve and where we want virtual reality to eventually get," said Zuckerberg during his keynote at the recent Oculus Connect. "It’s this feeling of real presence, like you’re really there with another person." This week Oculus, which is owned by Facebook, released Touch Controllers for its Rift VR system, allowing users to integrate more of their body into virtual space. But the technology has a long way to go.

"Making social interactions in VR as natural as the ones we’re used to in the real world is one of the grand technological challenges today," said Sheikh, speaking at this year’s F8 conference. "It’s a challenge because there is nothing people are more keenly aware of than other people. So the bar for deeply convincing virtual interactions is extremely high. But for the same reason, once that bar is reached, lifelike virtual interactions will be a transformative achievement, vastly extending our personal world, and connecting the world together in a way we haven’t seen before."

During my trip to the Panoptic Studio, Simon and another research assistant took me through one of the exercises the team uses to collect data. Standing inside the geodesic dome, we played a game called Ultimatum, in which three participants haggle over how to split 10 dollars. For anyone to receive money, all three have to agree on how it’s shared. It’s a classic experiment in economics and game theory, with participants trying to weigh how much they can squeeze out for themselves without losing everything by failing to reach a consensus.

Roughly two-thirds of what we communicate with one another comes through nonverbal cues

It’s also a great opportunity to study body language. The three of us stood face to face, two aligned against one. As we bargained back and forth for several minutes, we were constantly shifting our postures, gaze, and position from one another. During the negotiations I tried to project confidence, but the results spoke for themselves: I ended up taking home two dollars, while my hosts pocketed four bucks each.

After the game, we left the dome and headed to a bank of computers to review the footage. I could watch a replay of our conversation from 500 different angles, and they all told the same story. I began with an aggressive pose, my hands splayed in front, body squared, eyes fixed on the duo I was bargaining with. But as the game progressed I began fidgeting, rubbing my wrists, stepping backwards, and looking down at my shoes.

Your body often expresses inconvenient truths that your words are meant to mask, said Simon. "If what I’m saying doesn’t agree with the way I’m saying it, or what I’m doing, people will almost always listen to your body motion, or your non-verbal behavior, rather than your words." Decades of academic research have confirmed this primacy of body language, with scholars estimating that roughly two-thirds of what we communicate with one another comes through nonverbal cues.

Body language is a deeply instinctual: children as young as one or two years old can understand social cues from facial expressions and posture. And scientific experiments have demonstrated that individuals who are blind from birth will gesture when they talk, even though they have never learned to gesture from watching others.

Our minds are so primed to pick up on body language that we can recognize signals even when shown only the most basic outline of the human form. A number of academic studies have shown that people can distinguish biological motion from mechanical motions with just 20 points on a screen. "Our brains are remarkable inference engines, able to draw upon millennia of evolution and a lifetime of experience to transform these sparse points into fleshed out people in our imagination, and to predict the next actions of those imagined people as well," said Sheikh during Facebook’s F8 conference. "The challenge of making the pipeline of social VR work is to learn how to computationally do the same sort of inference and prediction."

Something as simple as a stare can convey anger, lust, or confusion

Artificial intelligence has made huge strides over the past decade in learning to understand what people are saying and how to respond. It can even best human experts when it comes to reading lips. But body language is much messier. To illustrate the problem Sheikh likes to show two close-up photographs of tennis player Rafael Nadal. In one, Nadal is experiencing a moment of anguish, in the other, ecstasy. But with just his face, it’s hard to know which is which. To clarify we need to zoom out, to read his entire posture, his hands, the full picture of a human. Something as simple as a stare can convey anger, lust, or confusion with only the subtlest of changes to the rest of your body.

The pillars of body language are facial expressions, gestures, posture, and gaze. Humans have tried since the beginning to work these elements into our digital communications. Emoticons were the most basic. A wink or a frown, while crude, can add an emotional effect to an email that would be difficult to impart with words. This was followed by decades of work on digital avatars with bodies that could express our intentions.

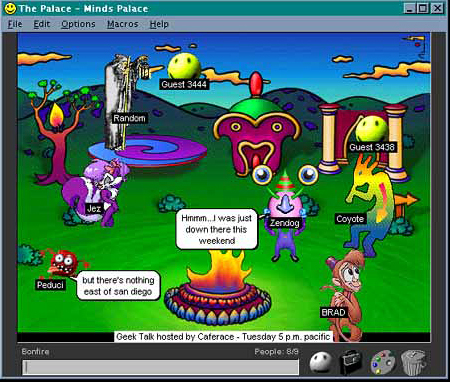

In the mid 1980s Habitat, a game developed by LucasArts, let players use keyboard commands to change their avatars’ facial expressions. In the early 1990s, startups like Traveler, DreamScape, WorldsAway, and The Palace all competed for users to populate their virtual worlds. WorldsAway users could walk and gesture and talk through speech bubbles. Later worlds, like There.com, added voice chat, and used the volume of your voice to activate certain gestures.

The dot-com crash wiped out most of this generation’s virtual worlds. "By 2000, it was all dead," said Bruce Damer, a historian of the period. There were a few exceptions to that rule. Dedicated communities of millions did coalesce around virtual worlds like The Sims and Second Life. Avatars in Second Life had 19 opposable joints, and users could manipulate them to create unique gestures. This led to a lot of awkward movements, as parodied in this classic YouTube video. Body language was such a desired commodity that users even paid for "animation overrides," or AOs, a sort of software mod that replaced standard movements with specially scripted ones.

The creators of these virtual worlds had imagined that one day everyone would use avatars to meet, shop, and fall in love online. But a year after Second Life launched, Facebook began to percolate across college campuses. It was a sort of evolutionary reset. In place of a highly detailed 3D avatar, your online identity was a photo and some text.

With Facebook’s purchase of Oculus in 2014, those two approaches to a social internet are coming together. Facebook and others in the VR space are returning to the pursuit of highly virtual avatars that had been largely abandoned with the bursting of the dot-com bubble. Only this time, the technology is ready. The sensors and cameras needed for good positional tracking had been developed inside gaming consoles and smartphones, ready to capture not just our voices and keyboard commands, but the actual movements of our bodies. Instead of "manipulating a character like a marionette," says Ebbe Altberg, CEO of Second Life creator Linden Lab. In VR, "it’s like wearing the skin of the avatar."

In 2015 Mike Booth, a 20-year veteran of the gaming industry, went to see a demo of a new virtual reality experience. He was invited by his friend, Jason Holtman, another gaming industry vet, who had recently secured a job at Oculus. Booth had vast experience with cutting-edge graphics and multiplayer games that let people interact online. But what he saw that day blew him away. It was a demo of Toybox, a simple social VR experience that puts two people together in a virtual playpen. "There were these floating blue hands and head that looked nothing like Jason. But it was Jason, because it picked up his biological motion, his nuances, the way his head nods."

Holtman’s avatar had no body, no facial features, no hair, none of the intricate details that Booth was used to from his work in the gaming industry. "I’ve been making video games for 20 years, and I’ve seen all kinds of stuff. The highest level triple AAA most realistic graphics, all that jazz. And all my career has been multiplayer online, so I’m very used to being with other people in online space. But that experience with Jason, I was literally speechless, and that’s what’s driven me to do social VR."

Booth is now leading Facebook’s efforts to create social VR, an extension of the service used by more than a billion people every day. The team’s first challenge was to craft avatars. "We thought, ‘Hey let’s just use photographs and rebuild a three-dimensional model of your actual head.’" In theory, everyone with a cell phone or webcam could then easily get a detailed, personalized representation of themselves. In practice, the idea was a disaster. A steely eyed photograph, stretched over a humanoid skull moving semi-naturally created, Booth says, a "dead head."

This problem, dubbed the Uncanny Valley, is common across the film and gaming industries, and even crops up in robotics: people generally like representations of humans the more lifelike they become. But cross a certain threshold, and suddenly we find that same character spooky. Part of our brain believes it’s a real person, while other parts are screaming it’s not.

"If you take something that’s remotely realistic, and you add that biological motion, you reach that Uncanny Valley much quicker than we expected," says Booth. "They’re not breathing right, their eyes don’t move right, they don’t look in the right spot. They’re psychotic!"

The very limited avatars Oculus had crafted for Toybox were a clever hack around this issue. "Number one, it’s blue — not a biological color. The eyes are hidden behind a visor, there is no mouth that animates," says Booth. "When those cues aren’t there, you focus on the cues that work."

"I wanted my friends to be able to smile or look confused."

But for Facebook, Booth wanted something more appealing than a blue bobblehead. "I really wanted to get eye contact, lip-synch, and expressions. I wanted my friends to be able to smile or look confused," says Booth. Most importantly, he wanted users to be able to recognize their close friends.

In April of this year, Booth and his team revealed an early experiment. They took the floating blue hands and head from Toybox, but allowed users to draw on personal details. Booth was distinguished by his receding hairline, goatee, and glasses. He sketched a tie for himself and attached it below his head, at the bottom of a nonexistent neck. It was rudimentary, a literal line drawing, but it added a world of character to his avatar.

Six months later, at Oculus Connect in October, Booth’s team had made huge strides. Facebook’s avatars now had arms and torsos. They could make eye contact, and their mouths moved to a rough approximation of their words when they spoke. The highlight was what Booth calls "gestural emotes," emotions triggered by specific postures. Booth compares it to the overblown movements of vaudeville actors. Bring your hands up to your cheeks and your avatar will gape like Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone. Pump your fists above your head and your avatar will break into a huge grin.

To get to this point, Booth and his team had to fudge reality. The position of an avatar’s arms is just an educated guess based on the movement of their hands and head. So is the direction of your gaze. In the virtual space you can see other people’s arms, but not your own — the engineers figured seeing your digital arms in one position, but feeling your physical arms in another, would have been too jarring. "We’re making judgement calls on what we think we can get away with that will enhance the feeling of being there with a real person," explains Booth. In the absence of technology that can truly capture body language, the team is building its best approximation. "The science wasn’t in yet, so I’m just gonna wing it."

Two of the most prominent platforms emerging for social VR alongside Facebook are AltspaceVR, an independent startup, and Oculus, which is owned by Facebook, but has its own avatar system. Interestingly, both take nearly opposite approaches to conveying body language. They studiously avoid the tricks Booth and his team use to improvise the things they cannot track: arms, mouth movement, and gaze. Instead, they stick almost religiously to what they can track with great fidelity, trusting our imagination to fill in the rest.

A few weeks after F8, I chatted with Eric Romo, the founder and CEO of AltspaceVR. I was in New York wearing an HTC Vive headset and holding a pair of motion controllers. Romo was in California doing the same. A pair of laser-emitting boxes affixed to the walls mapped the rooms we were in and tracked our motion, allowing Romo and I to walk, wave, and interact as if we were in the same space, and not 3,000 miles apart. If we got too close to one another in the virtual space, I felt legitimately uncomfortable. It was easier to avoid talking over one another, because hands gestures and head position provided conversational cues.

Compared with Facebook’s avatars, our body language was limited. We were like children’s action figures, given just enough mobility to spark the imagination. Our bodies had arms and hands, but they stayed locked at our sides. Our actual hand position was represented by a pair of controllers floating in front of our avatars. We had legs, but we couldn’t walk around. Instead we used a cursor to teleport from one position to another. Our heads moved, but our gaze did not. Our mouths didn’t attempt to track the sounds of our words.

We were like children’s action figures, given just enough mobility to spark the imagination

Romo explained that, for now at least, AltspaceVR was staying away from the methods Facebook is using to approximate the movement of your arms or mouth. "The research on this from the last decade is that it’s easier to make an emotional connection with an abstract avatar where everything you see is tracked and rendered correctly, versus trying to make an emotional connection with a very detailed avatar that is not being captured in the right way," he explained.

As more accurate tracking technology becomes available, AltspaceVR plans to add it in. Right now, for example, anyone with a Leap Motion controller can have highly detailed hands, complete with flexible fingers, in place of two floating game controllers. When comedians perform for big crowds in AltspaceVR, they can wear a full body suit, allowing them to act out physical gags.

Oculus takes a similar approach. "We were very clear early on that we wanted to avoid the temptation to add motion above and beyond what we could do with our track data," said Mike Howard, product manager at Oculus, during a recent talk. "There is a lot we could fake, from elbows, to knees, to the mouth, to eye movement… at best they distract from the real movement that the user is trying to convey, and at worst they get it wrong, and they don’t match what’s being said." The first ground rule of avatar design for Oculus is simple. "Leave it to the human brain, don’t fake it."

Yaser Sheikh, director of the Panoptic Studio, has nothing against cartoon avatars. "I think this is great work, and it’s certainly what the first wave of social VR will be like. But my personal research goal, and the goal of our lab in Pittsburgh, is to do photorealistic social VR," he explained. "It should feel as if, when I put on the headset, and you put on the headset in NY, we are in the same room, you look exactly the way you do, you move exactly the way you do."

By feeding thousands of hours of social interaction from the Panoptic Lab into deep learning algorithms, Sheikh believes he can teach computers to understand the subtleties of our body language, just as others have taught computers to understand spoken language, or to read lips. "When we look at a video of another person, the amount of information that hits our eyes and reaches our brain is actually quite impoverished. The reason we are able to suck out so much information from this is because we have a lifetime of experience interacting with people, and a rich repository of data in our mind," he explained. "The goal is to give machines that kind of imagination, that repository of data to draw on."

The better computers get at understanding our bodies, the less hardware tracking will require. "Obviously, as much as we want to, we’re not going to have 500 cameras set up in everyone’s living room," said Sheikh with a laugh. "What we want to do in the lab is get the sort of data that we need to build representations that will then drive measurement from much reduced capture setups, fewer cameras, and so on."

"The real promise of VR, in my opinion, is that it holds the potential of allowing us to build and grow relationships from distances."

Once social VR cracks the elaborate code and avatars are as convincing as actual people, a whole world of possibilities opens up: imagine an online dating service that lets you converse with potential matches across candlelit table before you meet up in real life. Or playing poker with a group of friends spread across the country, and being able to tell if a buddy is bluffing from his body language. Sheikh’s extended family lives in Abu Dhabi, and he sees social VR as a way to strengthen those ties. "The bond with the grandparents and the extended family just isn’t the same as if we were there. The real promise of VR, in my opinion, is that it holds the potential of allowing us to build and grow relationships from distances."

Of course, with convincing body language now a matter of computer code, the person across from you may not be what they seem. Imagine you’re in a boring meeting with a lot of people: in real life it would be rude to walk out the door. In VR you can sneak away, while your avatar stays sitting, nodding intelligently, and paying attention. "That autopilot version of a person I’m sure everyone would love to have," says Sheikh.

This kind of embellishment could be used for good. The Virtual Human Interaction Lab found students were more attentive and retained more material when the avatar representing the teacher was coded so that it appeared to each member of the class to be gazing directly at them. No regular teacher could simultaneously be looking at every student, but in VR, those limitations don’t exist.

After my visit to the Panoptic Studio, I wanted to try the cutting edge of social VR for myself. So a few months later I traveled to Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, where I got a demo of its Toybox software. Inside a windowless room optimized for virtual reality, I donned the Oculus headset and an assistant placed the Touch controllers in my hand. Now I was across a table from my partner, a pair of floating blue hands and a head.

In Toybox, I had the visceral sensation of being with another human being, but the world had none of the constraints or consequences you find in your living room. We could smash a vase with our slingshot, then snap a finger and it would be back. At one point we lowered the effects of gravity, and sent our pile of blocks floating in every direction. They scattered to the four corners of our playspace, and a few minutes later, reappeared neatly where they had begun.

My most vivid memory is of the moment we worked together to pick up a castle made of blocks. It required delicate coordination, and the physics of the wobbly structure pressed between our virtual fingers was so convincing that I could almost feel the weight in my hands.

There is an irony to to the notion that in the near future, some of our most exciting social interactions might happen when we’re shutting out the world. I imagined my own sons getting lost in this fantastic universe, and how wonderful a tool it could be for connecting if they found themselves living apart. Conversely I thought of how strange it would feel to come home find them sitting across from each other in our living room, each wearing a VR headset, alone together in another world.

We are social animals, and there is something intoxicating about being with another person in a virtual realm where earthly rules don’t apply. VR promises to connect us in a more intimate way than any technology has before, allowing for new forms of collaboration and creation. Eventually our avatars may come to feel like richer representations of who we are, or want to be. At that point, we’ll have to be careful not to get lost in our virtual worlds, and forget the bodies we’re leaving behind.

Editor: Michael Zelenko

Design: James Bareham

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13088567/tconnors_160523_1301_0026.0.0.1484223272.jpeg)

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13088567/tconnors_160523_1301_0026.0.0.1484223272.jpeg)

Share this story