Not long ago, I stepped into a lift on the 18th floor of a tall building in New York City. A young woman inside the lift was looking down at the top of her toddler’s head with embarrassment as he looked at me and grinned. When I turned to push the ground-floor button, I saw that every button had already been pushed. Kids love pushing buttons, but they only push every button when the buttons light up. From a young age, humans are driven to learn, and learning involves getting as much feedback as possible from the immediate environment. The toddler who shared my elevator was grinning because feedback – in the form of lights or sounds or any change in the state of the world – is pleasurable.

But this quest for feedback doesn’t end with childhood. In 2012, an ad agency in Belgium produced an outdoor campaign for a TV channel that quickly went viral. The campaign’s producers placed a big red button on a pedestal in a quaint square in a sleepy town in Flanders. A big arrow hung above the button with a simple instruction: Push to add drama. You can see the glint in each person’s eye as he or she approaches the button – the same glint that came just before the toddler in my elevator raked his tiny hand across the panel of buttons.

Psychologists have long tried to understand how animals respond to different forms of feedback. In 1971, a psychologist named Michael Zeiler sat in his lab across from three hungry white carneaux pigeons. At this stage, the research programme focused on rats and pigeons, but it had lofty aims. Could the behaviour of lower-order animals teach governments how to encourage charity and discourage crime? Could entrepreneurs inspire overworked shift workers to find new meaning in their jobs? Could parents learn how to shape perfect children?

Before Zeiler could change the world, he had to work out the best way to deliver rewards. One option was to reward every desirable behaviour. Another was to reward those same desirable behaviours on an unpredictable schedule, creating some of the mystery that encourages people to buy lottery tickets. The pigeons had been raised in the lab, so they knew the drill. Each one waddled up to a small button and pecked persistently, hoping that the button would release a tray of Purina pigeon pellets. During some trials, Zeiler would programme the button so it delivered food every time the pigeons pecked; during others, he programmed the button so it delivered food only some of the time. Sometimes the pigeons would peck in vain, the button would turn red, and they would receive nothing.

When I first learned about Zeiler’s work, I expected the consistent schedule to work best. But that’s not what happened at all. The results weren’t even close: the pigeons pecked almost twice as often when the reward wasn’t guaranteed. Their brains, it turned out, were releasing far more dopamine when the reward was unexpected than when it was predictable. Zeiler had documented an important fact about positive feedback: that less is often more. His pigeons were drawn to the mystery of mixed feedback just as humans are attracted to the uncertainty of gambling.

Decades after Zeiler published his results, in 2012, a team of Facebook web developers prepared to unleash a similar feedback experiment on hundreds of millions of humans. The site already had 200 million users at the time – a number that would triple over the next three years. The experiment took the form of a deceptively simple new feature called a “like button”.

It’s hard to exaggerate how much the like button changed the psychology of Facebook use. What had begun as a passive way to track your friends’ lives was now deeply interactive, and with exactly the sort of unpredictable feedback that motivated Zeiler’s pigeons. Users were gambling every time they shared a photo, web link or status update. A post with zero “likes” wasn’t just privately painful, but also a kind of public condemnation: either you didn’t have enough online friends, or, worse still, your online friends weren’t impressed. Like pigeons, we’re more driven to seek feedback when it isn’t guaranteed. Facebook was the first major social networking force to introduce the like button, but others now have similar functions. You can like and repost tweets on Twitter, pictures on Instagram, posts on Google+, columns on LinkedIn, and videos on YouTube.

The act of liking became the subject of etiquette debates. What did it mean to refrain from liking a friend’s post? If you liked every third post, was that an implicit condemnation of the other posts? Liking became a form of basic social support – the online equivalent of laughing at a friend’s joke in public.

Web developer Rameet Chawla developed an app as a marketing exercise, but also a social experiment, to uncover the effect of the like button. When he launched it, Chawla posted this introduction on its homepage: “People are addicted. We experience withdrawals. We are so driven by this drug, getting just one hit elicits truly peculiar reactions. I’m talking about likes. They’ve inconspicuously emerged as the first digital drug to dominate our culture.”

Chawla’s app, called Lovematically, was designed to automatically like every picture that rolled through its users’ newsfeeds. It wasn’t even necessary to impress them any more; any old post was good enough to inspire a like. Apart from enjoying the warm glow that comes from spreading good cheer, Chawla – for the first three months, the app’s only user – also found that people reciprocated. They liked more of his photos, and he attracted an average of 30 new followers a day, a total of almost 3,000 followers during the trial period. On Valentine’s Day 2014, Chawla allowed 5,000 Instagram users to download a beta version of the app. After only two hours, Instagram shut down Lovematically for violating the social network’s terms of use.

“I knew way before launching it that it would get shut down by Instagram,” Chawla said. “Using drug terminology, you know, Instagram is the dealer and I’m the new guy in the market giving away the drug for free.”

Chawla was surprised, though, that it happened so quickly. He’d hoped for at least a week of use, but Instagram pounced immediately.

When I moved to the United States for postgraduate studies in 2004, online entertainment was limited. These were the days before Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube – and Facebook was limited to students at Harvard. One evening, I stumbled on a game called Sign of the Zodiac (Zodiac for short) that demanded very little mental energy.

Zodiac was a simple online slot machine, much like the actual slot machines in casinos: you decided how much to wager, lazily clicked a button over and over again, and watched as the machine spat out wins and losses. At first, I played to relieve the stress of long days filled with too much thinking, but the brief “ding” that followed each small win, and the longer melody that followed each major win, hooked me fast. Eventually screenshots of the game would intrude on my day. I’d picture five pink scorpions lining up for the game’s highest jackpot, followed by the jackpot melody that I can still conjure today. I had a minor behavioural addiction, and these were the sensory hangovers of the random, unpredictable feedback that followed each win.

My Zodiac addiction wasn’t unusual. For 13 years, Natasha Dow Schüll, a cultural anthropologist, studied gamblers and the machines that hook them. She collected descriptions of slot machines from gambling experts and current and former addicts, which included the following: “Slots are the crack cocaine of gambling … electronic morphine ... the most virulent strain of gambling in the history of man … Slots are the premier addiction delivery device.”

These are sensationalised descriptions, but they capture how easily people become hooked on slot-machine gambling. I can relate, because I became addicted to a slots game that wasn’t even doling out real money. The reinforcing sound of a win after the silence of several losses was enough for me.

In the US, banks are not allowed to handle online gambling winnings, which makes online gambling practically illegal. Very few companies are willing to fight the system, and the ones that do are quickly defeated. That sounds like a good thing, but free and legal games such as Sign of the Zodiac can also be dangerous. At casinos, the deck is stacked heavily against the player; on average the house has to win. But the house doesn’t have to win in a game without money.

As David Goldhill, the chief executive officer of the Game Show Network, which also produces many online games, told me: “Because we’re not restricted by having to pay real winnings, we can pay out $120 for every $100 played. No land-based casino could do that for more than a week without going out of business.” As a result, the game can continue forever because the player never runs out of chips. I played Sign of the Zodiac for four years and rarely had to start a new game. I won roughly 95% of the time. The game only ended when I had to eat or sleep or attend class in the morning. And sometimes it didn’t even end then.

Casinos win most of the time, but they have a clever way of convincing gamblers that the outcomes are reversed. Early slot machines were incredibly simple devices: the player pulled the machine’s arm to spin its three mechanical reels. If the centre of the reels displayed two or more of the same symbol when they stopped spinning, the player won a certain number of coins or credits. Today, slot machines allow gamblers to play multiple lines. Every time you play, you’re more likely to win on at least one line, and the machine will celebrate with you by flashing bright lights and playing catchy tunes. If you play 15 lines, and you win on two of the lines, you make a net loss, and yet you enjoy the positive feedback that follows a win – a type of win that Schüll and other gambling experts call a “loss disguised as a win”.

Losses disguised as wins only matter because players don’t classify them as losses – they classify them as wins. This is what makes modern slot machines – and modern casinos – so dangerous. Like the little boy who hit every button in my lift, adults never really grow out of the thrill of attractive lights and sounds. If our brains convince us that we’re winning even when we’re actually losing, it becomes almost impossible to muster the self-control to stop playing.

The success of slot machines is measured by “time on device”. Since most players lose more money the longer they play, time on device is a useful proxy for profitability. Video-game designers use a similar measure, which captures how engaging and enjoyable their games are. The difference between casinos and video games is that many game designers are more concerned with making their games fun than with making buckets of money. Bennett Foddy, who teaches game design at New York University’s Game Center, has created a number of successful free-to-play games, but each was a labour of love rather than a money-making vehicle.

“Video games are governed by microscopic rules,” Foddy says. “When your mouse cursor moves over a particular box, text will pop up, or a sound will play. Designers use this sort of micro-feedback to keep players more engaged and more hooked in.”

A game must obey these microscopic rules, because gamers are likely to stop playing a game that doesn’t deliver a steady dose of small rewards that make sense given the game’s rules. Those rewards can be as subtle as a “ding” sound or a white flash whenever a character moves over a particular square. “Those bits of micro-feedback need to follow the act almost immediately, because if there’s a tight pairing in time between when I act and when something happens, then I’ll think I was causing it.”

The game Candy Crush Saga is a prime example. At its peak in 2013, the game generated more than $600,000 in revenue per day. To date, its developer, King, has earned around $2.5 billion from the game. Somewhere between half a billion and a billion people have downloaded Candy Crush Saga on their smartphones or through Facebook. Most of those players are women, which is unusual for a blockbuster.

It’s hard to understand the game’s colossal success when you see how straightforward it is. Players aim to create lines of three or more of the same candy by swiping candies left, right, up, and down. Candies are “crushed” – they disappear – when you form these matching lines, and the candies above them drop down to take their place. The game ends when the screen fills with candies that cannot be matched. Foddy told me that it wasn’t the rules that made the game a success – it was juice. Juice refers to the game’s surface feedback. It isn’t essential to the game, but it’s essential to the game’s success. Without juice, the game loses its charm.

“Novice game designers often forget to add juice,” Foddy said. “If a character in your game runs through the grass, the grass should bend as he runs through it. It tells you that the grass is real and that the character and grass are in the same world.” When you form a line in Candy Crush Saga, a reinforcing sound plays, the score associated with that line flashes brightly, and sometimes you hear words of praise intoned by a hidden, deep-voiced narrator.

Juice amplifies feedback, but it’s also designed to unite the real world and the gaming world. The most powerful vehicle for juice must surely be virtual reality (VR) technology, which is still in its infancy. VR places the user in an immersive environment, which the user navigates as she might the real world. Advanced VR also introduces multisensory feedback, including touch, hearing and smell.

In a podcast last year, the author and sports columnist Bill Simmons spoke to billionaire investor Chris Sacca, an early Google employee and Twitter investor, about his experience with VR. “I’m afraid for my kids, a little bit,” Simmons said. “I do wonder if this VR world you dive into is almost superior to the actual world you’re in. Instead of having human interactions, I can just go into this VR world and do VR things and that’s gonna be my life.”

Sacca shared Simmons’ concerns. “One of the things that’s interesting about technology is that the improvement in resolution and sound modelling and responsiveness is outpacing our own physiological development,” Sacca said. “You can watch some early videos … where you are on top of a skyscraper, and your body will not let you step forward. Your body is convinced that that is the side of the skyscraper. That’s not even a super immersive VR platform. So we have some crazy days ahead of us.”

Until recently, most people thought of VR as a tool for gaming, but that changed when Facebook acquired Oculus VR for $2bn in 2014. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg had big ideas for the Oculus Rift gaming headset that went far beyond games. “This is just the start,” Zuckerberg said. “After games, we’re going to make Oculus a platform for many other experiences. Imagine enjoying a court-side seat at a game, studying in a classroom of students and teachers all over the world or consulting with a doctor face-to-face – just by putting goggles in your home.” VR no longer dwelled on the fringes. “One day, we believe this kind of immersive, augmented reality will become a part of daily life for billions of people,” said Zuckerberg.

In October 2015, the New York Times shipped a small cardboard VR viewer with its Sunday paper. Paired with a smartphone, the Google Cardboard viewer streamed VR content, including documentaries on North Korea, Syrian refugees, and a vigil following the Paris terror attacks. “Instead of sitting through 45 seconds on the news of someone walking around and explaining how terrible it is, you are actively becoming a participant in the story that you are viewing,” said Christian Stephen, a producer of one of the VR documentaries.

Despite the promise of VR, it also poses great risks. Jeremy Bailenson, a professor of communication at Stanford’s Virtual Reality Interaction Lab, worries that the Oculus Rift will damage how people interact with the world. “Am I terrified of the world where anyone can create really horrible experiences? Yes, it does worry me. I worry what happens when a violent video game feels like murder. And when pornography feels like sex. How does that change the way humans interact, function as a society?”

When it matures, VR will allow us to spend time with anyone in any location doing whatever we like for as long as we like. That sort of boundless pleasure sounds wonderful, but it has the capacity to devalue face-to-face interactions. Why live in the real world with real, flawed people when you can live in a perfect world that feels just as real? Wielded by game designers, it might prove to be a vehicle for the latest in a series of escalating behavioural addictions.

Some experiences are designed to be addictive for the sake of ensnaring hapless consumers, but others happen to be addictive though they are primarily designed to be fun or engaging. The line that separates these is very thin; to a large extent the difference rests on the intention of the designer.

When Nintendo’s superstar game designer Shigeru Miyamoto created Super Mario Bros, his primary aim was to make a game that he himself enjoyed playing. “That’s the point,” he said, “not to make something sell, something very popular, but to love something, and make something that we creators can love. It’s the very core feeling we should have in making games.”

When you compare Super Mario Bros – regularly voted by game designers as one of the greatest games ever – to others on the market, it is easy to recognise the difference in intention.

Adam Saltsman, who produced an acclaimed indie game called Canabalt in 2009, has written extensively about the ethics of game design. “Many of the predatory games of the past five years use what’s known as an energy system,” Saltsman said. “You’re allowed to play the game for five minutes, and then you artificially run out of stuff to do. The game will send you an email in, say, four hours when you can start playing again.” I told Saltsman that the system sounded pretty good to me – it forces gamers to take breaks and encourages kids to do their homework between gaming sessions. But that’s where the predatory part comes in.

According to Saltsman: “Game designers began to realise that players would pay $1 to shorten the wait time, or to increase the amount of energy their avatar would have once the four-hour rest period had passed.” I came across this predatory device when playing a game called Trivia Crack. If you give the wrong answer several times, you run out of lives, and a dialogue screen gives you a choice: wait for an hour for more lives, or pay 99 cents to continue immediately. Many games hide these down-the-line charges. They’re free, at first, but later you are forced to pay in-game fees to continue.

If you are minutes or even hours deep into the game, the last thing you want to do is admit defeat. You have so much to lose, and your aversion to that sense of loss compels you to feed the machine just one more time, over and over again. You start playing because you want to have fun, but you continue playing because you want to avoid feeling unhappy.

A game in which you always win is boring. It sounds appealing but it gets old fast. To some extent we all need losses and difficulties and challenges, because without them the thrill of success weakens gradually with each new victory. The hardship of the challenge is far more compelling than knowing you are going to succeed. This sense of hardship is an ingredient in many addictive experiences, including one of the most addictive games of all time: Tetris.

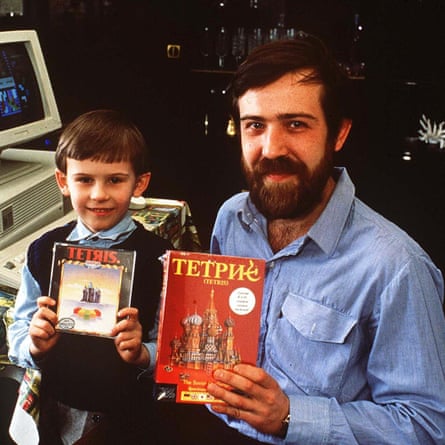

In 1984, Alexey Pajitnov was working at a computer lab at the Russian Academy of Science in Moscow. Many of the lab’s scientists worked on side projects, and Pajitnov began working on a video game. Pajitnov worked on Tetris for much longer than he planned because he couldn’t stop playing the game. Eventually Pajitnov allowed his friends at the Academy of Science to play the game. “Everyone who touched the game couldn’t stop playing either.”

His best friend, Vladimir Pokhilko, a former psychologist, remembered taking the game to his lab at the Moscow Medical Institute. “Everybody stopped working. So I deleted it from every computer. Everyone went back to work, until a new version appeared in the lab.”

Tetris spread from the Academy of Science to the rest of Moscow, and then on to the rest of Russia and eastern Europe. Two years later, in 1986, the game reached the west, but its big break came in 1991, when Nintendo signed a deal with Pajitnov. Every Game Boy would come with a free game cartridge that contained a redesigned version of Tetris.

That year I saved up and ultimately bought a Game Boy, which is how I came to play Tetris for the first time. It wasn’t as glitzy as some of my other favourites, but I played for hours at a time. Nintendo was smart to include the game with their new portable console, because it was easy to learn and very difficult to abandon. I assumed that I would grow tired of Tetris, but sometimes I still play the game today, more than 25 years later. It has longevity because it grows with you. It’s easy at first, but as your skills improve, the game gets more difficult. The pieces fall from the top of the screen more quickly, and you have less time to react than you did when you were a novice.

This escalation of difficulty is a critical hook that keeps the game engaging long after you have mastered its basic moves. Twenty-five years ago, a psychiatrist named Richard Haier showed that this progression is pleasurable because your brain becomes more efficient as you improve. Haier decided to watch as people mastered a video game, though he knew little about the cutting-edge world of gaming. “In 1991 no one had heard of Tetris,” he said in an interview a few years later. “I went to the computer store to see what they had and the guy said, ‘Here try this. It’s just come in.’ Tetris was the perfect game, it was simple to learn, you had to practise to get good, and there was a good learning curve.”

Haier bought some copies of Tetris for his lab and watched as his experimental subjects played the game. He did find neurological changes with experience – parts of the brain thickened and brain activity declined, suggesting experts’ brains worked more efficiently – but more relevant here, he found that his subjects relished playing the game. They signed up to play for 45 minutes a day, five days a week, for up to eight weeks. They came for the experiment (and the cash payment that came with participating), but stayed for the game.

One satisfying feature of the game is the sense that you are building something – your efforts produce a pleasing tower of coloured bricks. You have the chaos coming as random pieces, and your job is to put them in order. The game allows you the brief thrill of seeing your completed lines flash before they disappear, leaving only your mistakes. So you begin again, and try to complete another line as the game speeds up and your fingers are forced to dance across the controls more quickly.

Mikhail Kulagin, Pajitnov’s friend and a fellow programmer, remembers feeling a drive to fix his mistakes. “Tetris is a game with a very strong negative motivation. You never see what you have done very well, and your mistakes are seen on the screen. You always want to correct them.”

The sense of creating something that requires labour and effort and expertise is a major force behind addictive acts that might otherwise lose their sheen over time. It also highlights an insidious difference between substance addiction and behavioural addiction: where substance addictions are nakedly destructive, many behavioural addictions are quietly destructive acts wrapped in cloaks of creation. The illusion of progress will sustain you as you achieve high scores or acquire more followers or improve your skills, and so, if you want to stop, you’ll struggle ever harder against the drive to grow.

“Some designers are very much against infinite format games, like Tetris,” said Foddy, “because they’re an abuse of a weakness in people’s motivational structures – they won’t be able to stop.”

Humans find the sweet spot sandwiched between “too easy” and “too difficult” irresistible. It’s the land of just-challenging-enough computer games, financial targets, work ambitions, social media objectives and fitness goals. It is in this sweet spot – where the need to stop crumbles before obsessive goal-setting – that addictive experiences live.

This is an adapted extract of Irresistible by Adam Alter, published on 2 March by The Bodley Head in the UK and Penguin Press in the US on 7 March