When Will We Want to Be in a Room Full of Strangers Again?

Theater, an industry full of optimists, is reckoning with a heartbreaking realization.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of Uncharted, a series about the world we’re leaving behind, and the one being remade by the pandemic.

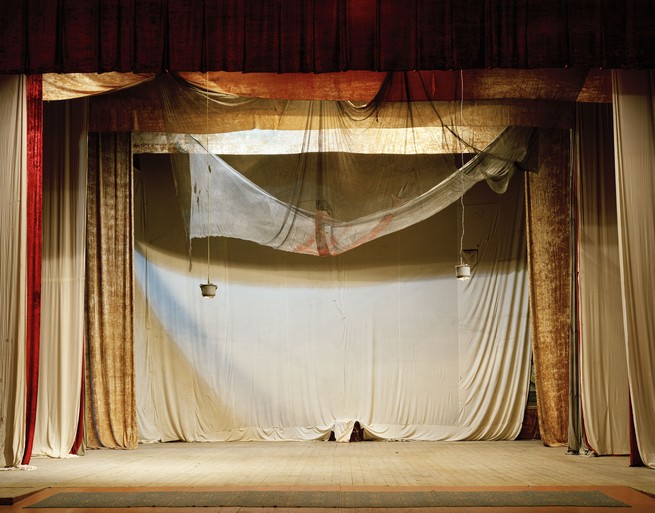

Walking into the Kiln Theatre in North London is like uncovering a time capsule—from before lockdown, before social distancing, before face masks and injunctions to stay six feet apart. When staff do their regular checks on the building, its artistic director, Indhu Rubasingham, told me, they say it feels “frozen,” caught in the moment before everything changed. “The stage is all set; the dressing rooms are ready for the actors to come in the next day,” she said.

Rubasingham is not alone in facing an uncertain future. In March, the government ordered theaters to shut, and no one yet knows when they will reopen. The Arts Council, which distributes state funding, quickly gave out £160 million ($200 million) in crisis grants to organizations and individual workers in need. In combination with the government’s furlough scheme—which offers to pay a portion of workers’ wages until the end of June—this has stabilized the industry. Just like the Kiln’s building, many projects and individual careers are frozen in time.

As a live art form, theater is particularly affected by the coronavirus, along with concerts and stand-up comedy performances. As I talked with writers, directors, and producers, the same refrain recurred: When will anyone want to be in a dark room full of strangers again? Many of those I spoke with were quietly updating their scenario-planning documents to account for a return next spring, and warned that, without a bailout, that long of a shutdown would financially cripple some institutions. Even when theaters reopen, social-distancing rules could hamper rehearsals, and force venues to sell fewer (and therefore more expensive) tickets. Most believe theater will eventually rebound, but there is talk of a generation of artists and audiences being lost. Rubasingham worries that the industry could become more white, more posh—and more cautious: “We’re going to be so much more fragile coming back, so do we become more risk-averse?”

Theater matters to Britain in purely economic terms; the West End is a significant driver of tourism. And although many see commercially run theaters and the subsidized sector as distinct, theater’s ecology is complicated and interconnected. The money-spinning West End is bolstered by projects that originated in the state-subsidized economy, such as the Royal Shakespeare Company’s musical Matilda, and you can trace a direct line from productions in smaller theaters in Britain and continental Europe through to Broadway. It is also a creative engine for the rest of the arts: film directors such as Sam Mendes, Stephen Frears, and Danny Boyle were nurtured there. James Graham, who won an Emmy for his drama Brexit: The Uncivil War, spent the early years of his career writing for the Finborough Theatre, a 50-seat room above a bar in West London. Lucy Prebble, who works on HBO’s Succession, had her first professional play staged by the subsidized Royal Court in its 90-seat studio. The Fleabag creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Alice Birch, the adapter of Normal People, also started out in theater. The Tudor musical Six (which had to shut down hours before it was due to open on Broadway, because of the coronavirus) began as a fringe show written by students, before going on tour around Britain. The same route—from tiny theaters to the commercial sector—has been followed by less visible workers, such as costume and set designers, as well.

The message from the industry is clear. If grassroots theater dies, what else dies with it?

The cost of “going dark” is significant. Nica Burns, whose company, Nimax, has six theaters in the West End, estimated that the lockdown would cost her business £2.5 million over three months. For the 800 museums, galleries, and theaters supported by the Arts Council, the monthly bailout bill—if the furlough scheme ends—will be £100 million. Few were surprised when Rufus Norris, the artistic director of the National Theatre, said in April that some organizations were “days, not weeks,” away from filing for bankruptcy. On May 6, Nuffield Southampton Theatres, in the south of England, announced that it had run out of cash.

“The National will survive,” Tamara Harvey, the artistic director of Theatr Clwyd, in northern Wales, told me. “My fear is that the smaller and regional companies who aren’t visible might be allowed to sink.” Many of those local theaters are also community centers, providing adult-education classes, activities for older people, and singing and acting lessons for children whose schools cannot provide them. This community spirit is obvious in those theaters that have repurposed themselves to tackle the pandemic fallout: The costume department at the Royal Exchange in Manchester has begun to sew masks for health workers; the tiny Slung Low theater in Leeds has been delivering food parcels; Theatr Clwyd has become a blood-donation center.

Many of these smaller sites rely on state subsidies to survive, but now face a painful struggle to secure financial support. The Conservative government has said little publicly during this crisis about the future of theater, but the party has historically taken a dim view of arts subsidy—its first budget after winning a general election a decade ago cut the Arts Council’s funding by nearly a third. And with the pandemic badly hitting other parts of society, the demands on the state are huge. Many outsiders might echo the Los Angeles Times theater critic Charles McNulty, who wrote recently: “Call me callous but the fate of our hospital system straining under the weight of desperately sick patients [seems] more urgent to me than the budgetary death spirals of experimental theater companies.” Money, and sympathy, are finite.

As well as a financial response to the pandemic, buildings and artists are trying to decide the best artistic one. The crisis has already prompted a scramble to find production methods that are coronavirus-compliant, and to make recorded productions available to watch from home. Nick Hytner of the Bridge Theatre in London is reviving Talking Heads, the classic British monologue series, for the BBC, with lone actors talking to the camera in a deserted television studio. (They have rehearsed over Zoom, and must do their own hair and makeup to maintain social-distancing rules.) The National Theatre has made filmed versions of much of its back catalog available to schools, and it broadcasts a different archive show on YouTube every week, alongside an appeal for donations—the first show, One Man, Two Guvnors, starring James Corden, had more than 200,000 viewers. Four London plays that closed early will now be broadcast on BBC Radio. There have also been numerous variety shows for charity, which seem to attract pun-based titles, such as All the Web’s a Stage and The Show Must Go Online.

Although everyone is publicly supportive of these efforts—and recognizes the need for fundraising—in private, there are grumbles. The big organizations, with their box-office hits and star casts, are best placed to drive traffic to their online shows, while smaller companies struggle (and may not have had the resources to film productions in the first place). The Talking Heads monologues will be professionally produced, for example, but there has also been a rash of homespun productions of varying technical competence, which are often unsatisfying as pieces of art. After all, what makes theater great—and worth anything up to £250 a ticket in the West End—is the electricity of a shared experience. On-screen, plays can seem static, and the kind of acting that reaches the back of an auditorium can look forced or hammy. Too often, recordings of plays just look like bad television. The film industry is experiencing some success with “lockdown premieres,” releasing movies directly to home streaming, but no one in theater has so far felt comfortable charging anything close to a full ticket price for a digital offering.

All that makes everyone keen to open their doors again. The government furlough scheme has been widely adopted in the theater sector—the Kiln, for example, has put 12 out of 26 permanent staff on paid leave, plus 45 front-of-house workers on short-term contracts. But the program is scheduled to end on June 30. (The government has suggested it will gradually wind it down to avoid suddenly making huge numbers of people unemployed, but no firm announcements have been made.) Without it, life will be very hard for the casual staff who keep playhouses going—the ushers, box-office staff, and bartenders—as well as for the actors, writers, and directors who typically work as freelancers.

The industry’s more privileged members will be best placed to weather the crisis. “If you come from a low socioeconomic background, or are an immigrant working here and your life here is already quite precarious, you go: I can’t take the risk anymore,” the critic Lyn Gardner told me. The playwright Barney Norris says that his father, a professional pianist, told him when he became a writer that he should take notice of the number of his peers who dropped out in their early 30s, as they decided to start a family. “There comes a moment when people who have been living their dream say, ‘I'm going to stop living my dream; now I’m going to get a pension,’” he told me. “That might well happen to the entire planet now, regardless of their age.”

The real financial crunch point comes if the shutdown lasts beyond November, when most theaters open their Christmas show—in Britain, this is traditionally a pantomime or other family-friendly offering. At local theaters and in the West End, audiences often book tickets for the Christmas show as early as February, and grandparents bring their grandchildren, instilling a theater-going habit that might last a lifetime. The loss of that revenue, and that chance to introduce youngsters to play-going, would be hugely destructive across the sector. This, too, could make theater more rarefied, as casual visitors are turned off the art form.

There are also already signs that Rubasingham’s worries about risk aversion are well founded. The first major post-lockdown project announced by Sonia Friedman Productions, a West End powerhouse, is a revival of Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem, with its original star, Mark Rylance. It’s as close to a banker as any production can be: The original sold out and transferred to Broadway. “People will want to get those tickets,” Gardner said. “That gets them over the psychological hurdle of returning to the theater.”

Aside from beloved landmark productions, what else will people want to see? Will they hunger for escapism, for farces and comedies and lighthearted romps, or will they expect playwrights to address the aftermath of the pandemic? “Comedy is fine, but catharsis is essential,” says Michael Grandage, a director who runs a West End production company. “It doesn’t matter if we can gather in a room and laugh. To me, it’s more important that we can gather in a room and cry. Frankly you could watch Hamlet right now, and find lots of COVID dilemmas—a man feeling lost in the world.” Barney Norris said that, so far, all the artistic directors he had spoken with were trying to honor their existing commitments, which would create an “interesting tension” between pre- and post-coronavirus commissions when shows resume—one person I talked to said an existing, and overtly political, project now felt oddly dated. On top of all that, the Arts Council’s funding requirements now place “relevance” over “excellence” as the highest goal of British theater. Everyone is dreading the inevitable onslaught of work full of overwrought plague metaphors, and the possibility of stand-up comedy shows called Now Wash Your Hands.

Several artistic directors I spoke with referred to the same nightmare scenario: of reopening too early, with all the associated costs of set design, front-of-house staff, and actors, only to have to close again weeks later were another lockdown put in place. Not only would they take a financial hit, but audiences might lose confidence about booking future performances. The West End relies heavily on visitors from outside London, and people often buy tickets for popular shows months, even years, in advance. The commercial-theater sector in particular is therefore largely downbeat about the prospect of reopening anytime this year. Investors won’t want to risk another shutdown, and the budgets simply don’t add up if houses are only half full, or less.

The budget issue is also why there is little appetite for the kind of social-distancing measures the government hopes will allow other businesses, such as shops and restaurants, to reopen. Theaters in countries with previous experience of pandemics, such as South Korea, have installed disinfection sprays and temperature checks on arrival, and face masks must be worn throughout performances. Every attendee’s personal information is recorded, so that if anyone present is diagnosed with COVID-19, everyone in the theater can be traced and quarantined.

The consensus here in London is that theatergoers simply won’t stand for this. “I started thinking about socially distanced rehearsal rooms, socially distanced staging—what that means in terms of costumes and makeup, not having any of that,” Harvey told me. “Do we have to have actors standing far apart?” She concluded it was impossible, and would risk the long-term future of the Theatr Clwyd, because a bad experience could put off audiences forever. Grandage was equally unenthused: “Ask any actor if they want to play to a half-empty house on a comedy, and they’ll tell you it’s not a very desirable thing to do.” The prospect of reopening in a global recession has also focused minds on ticket prices, which have risen by 30 percent since 2012.

One obvious way to cut costs is to reduce cast sizes. (“Hope you like Waiting for Godot,” a friend joked to me recently.) That helps theaters balance their books, but hurts actors. Revivals are often easier to sell—Chekhov and Ibsen are, in marketing terms, strong brands—but that hurts contemporary writers. And an overall reduction in programming hurts directors, too, most of whom are hired for individual projects rather than receiving a salary from an institution.

On May 1, the Arts Council warned that it does not have the money to bankroll the industry through an extended lockdown, nor “the ability to support the costs of reopening under changed circumstances.” Underneath the uplifting language—“through creativity and culture, we will heal”—the message was clear. We can’t save you. Unsurprisingly, there is now concerted lobbying of the government by artistic directors, and high-profile figures in the arts. The “Big 13” regional theaters in England have been coordinating their efforts over Zoom discussions, as have a group of senior national figures led by David Lan, the former artistic director of the Young Vic in London. If the shutdown continues into next year, their success or failure will determine what kind of industry emerges from the crisis. Yes, someone might be writing the modern equivalent of King Lear in lockdown. But who will commission it? And will they be told: Could you manage with just two daughters? And no storm?

There are flashes of positivity; most theater-makers describe themselves as natural optimists. “Someone right now is writing a really great play they wouldn’t have got round to,” Barney Norris told me. Then he added dejectedly, “But there’ll be no money.”