When a Company Invests in an ‘Underdog City’

The country is full of “underdog cities”—communities and regions that are aware of losing out and having been overlooked. Some are in Appalachia, some in the Deep South, some around the Great Lakes, some in inland regions of otherwise-prospering states in the West. The imbalances in American opportunity—by race, by gender, by neighborhood and region, by class and economics—are of fundamental importance in the politics of the past generation, and in the prospects for renewal in the generation ahead.

Today’s installment is the story of how a company that started in one of these places is now involving people and businesses in another—and why that matters in the next stage of equitable American recovery.

The company is Bitwise Industries; its site-of-origin is Fresno, in California’s agriculturally rich (but otherwise poor) Central Valley; and its latest project will be in the once-strong, recently troubled American manufacturing belt along the Great Lakes. This week, Bitwise announced a new $50 million venture to expand a model that has proven effect in California to other “underdog” parts of the country, starting with the city of Toledo, Ohio.

The money has come from private investors—Kapor Capital, JPMorgan Chase, Motley Fool Ventures, and the Toledo-based health-care non-profit ProMedica. Its announced goal, according to Bitwise, is “to support the actions needed to stop the widening wealth gap, end institutional discrimination, and remove the barriers for accessing high-wage, high-growth jobs.” In practice this means creating technology-training centers, incubators for startup businesses, partnerships with schools and universities, and in some cases physical renovations of run-down buildings.

The funding is based on Bitwise’s track record of success in expanding opportunities for tech-related jobs in under-served communities in California. Its first project, in Toledo, will be opening a new training, incubator, coworking, and apprenticeship center in a historic downtown structure that for years has stood vacant and decaying.

For Bitwise, this venture is an application of what its leaders call the “Digital New Deal”—opening more of this era’s opportunities to those who have lacked them. For Toledo it is, as the mayor, Wade Kapszukiewicz, put it to me, “a sign that the city is moving in the right direction,” and that people within the city “whose economic futures have been uncertain, they’ll have a chance to be on a better path.”

As always, whether this will pay off is unknowable. But it is based on ideas and practices that in other parts of the country have so far proved their worth.

Now, a word about the participants, their backgrounds, and the idea.

Fresno and Bitwise: Fresno is the largest city in the Central Valley, whose farms, vineyards, groves, and orchards are acre-for-acre some of the most valuable farmland in the world. But despite the area’s phenomenal productivity, the people of the valley are on average very poor by national standards, and subject to the educational, social, and health handicaps that accompany poverty. By some calculations, if California ever carried out a scheme to divide itself into six states—which it won’t—the resulting new state of Central California would be the very poorest in the Union.

Over the past six years, starting here and here and running through this last year, Deb Fallows and I have frequently reported on economic, civic, and cultural comeback activities in Fresno and the vicinity. One important economic and cultural driver there has been Bitwise. This was a startup firm when we first wrote about it, which has expanded into a combination of software house, tech-training center, and overall civic connector that has played a significant role in the city’s attempts at revival. (We’ve written about similar efforts from smaller tech companies in, for instance, Erie, Pennsylvania.) Deb and I have been impressed enough by their work that we’ve become paying customers of Bitwise on some web-design projects.

The company’s cofounders, Irma Olguin Jr. and Jake Soberal, have been explicit in saying that their goal is to expand tech-economy opportunities for individuals, families, communities, and regions that the larger tech boom has left behind. “Bitwise is a tech ecosystem, activating human potential to elevate underdog cities around the country,” the company says on its web site. “My grandmother came here from Mexico, and my grandfather grew up very poor,” Soberal told me, when I spoke with him and Olguin on the phone this week. Olguin herself grew up in a Central Valley field-working family. The opportunity to go to college, and to start a business in the tech industry, dramatically changed her prospects. She has spoken many times about the countless others who thirst for such opportunities, in the technology business that had traditionally been closed to people from backgrounds like hers.

In 2019, Bitwise raised $27 million in “Series A” startup money, mainly to expand beyond Fresno to other “underdog” cities in California, like Bakersfield, Merced, and Oakland. With this $50 million in new “Series B” money, it intends to go national, toward other places with similar challenges—and potential. “The spread of COVID-19 and events of 2020 exposed the deep flaws that have existed for decades in the United States, and laid bare the unsustainable nature of our current systems/policies, and how they trap people in a cycle of poverty,” Olguin said in a statement announcing the new funding. “The past year showed us that there is no time to waste and we need to be aggressive about driving change now.”

“We were really rolling in California, and began asking ourselves, if we were to expand further, where would we go next?” Jake Soberal told me. “We wanted to see where we could have maximum impact.” The answer turned out to be Toledo.

Toledo and ProMedica: What agriculture has been to Fresno’s economy, manufacturing has historically been to Toledo’s. This has especially been true for firms related to the auto industry in nearby Detroit, most notably in glass. Toledo’s nickname is “Glass City,” and it is still the headquarters of Owens-Illinois, Owens-Corning, Libbey, and other major glass makers.

But the city’s biggest employer is now a health-care organization—something that Deb and I found to be true in a strikingly large number of places. For Toledo, that organization is ProMedica, which operates hospitals, clinics, and doctors’ offices in the area, and senior-care centers in 26 states.

ProMedica is organized as a non-profit, and describes itself as a “health and well-being organization” with a commitment to reviving its local community. Its CEO, Randy Oostra, told me this week that “when you look at health outcomes, it’s 20 percent clinical care, 40 percent social determinants” (and the rest is other things). That is, to foster healthy patients, you need healthy communities.

“An emphasis on social determinants is in our DNA,” he said. “We see our mission as actively looking to improve people’s lives—which include people’s ability to learn, to get a job, to support healthy families.” He said that ProMedica also considered itself an “anchor institution” for the revival of Toledo as a whole. In 2017 it moved its headquarters to the downtown waterfront, where as part of a $60 million construction project it had renovated a huge old steam-power plant. In 2019 it contracted to buy from the city’s school board the huge, once-magnificent downtown structure that had been built in 1911 as the Main Post Office and, after a variety of incarnations, had fallen into disuse.

At a virtual conference last summer, Robin Whitney, ProMedica’s chief of strategic planning, heard Irma Olguin talk about Bitwise’s record in Fresno and its desire to bring its model to other cities. As it happened, Olguin had a connection to the city. After finishing high school in the Central Valley, she had got her computer-science degree in the early 2000s at the University of Toledo. Whitney got in touch and said, what about Toledo?

“They more we talked, the more we realized we were kindred spirits,” Robin Whitney told me. “The passion they had, the idea that you have to give more people a real opportunity, it was a match.”

“My having an understanding of that area was helpful,” Olguin told me, when I asked: Why Toledo? “When I was first there, I was young and inexperienced and didn’t have the experience of starting a company under my belt. But the conversations we have now, and the absolute thirst to uplift the city, make a lot more sense. Too many people feel they have been left out, and need a chance.”

“What people feel about Fresno, or Bakersfield, they feel about Toledo,” Jake Soberal said. “The underdog nature, the willingness to work together.” “Working together,” which sounds like a platitude, has been an important part of the Bitwise model: partnerships among city and state governments, universities, community groups and NGOs, and companies large and small, with a local focus. They felt that they found that level of connection in Toledo.

“I know it’s a cliche to say ‘win-win,’ but I think that’s what this project is, for all involved,” Mayor Kapszukiewicz, a Democrat first elected in 2017, told me about the project. “Whether or not you buy into the notion that everything between the East Coast and the West Coast is ‘flyover country,’”—and by the way, I don’t—“in the economy there are winners and losers. In this region, we have done a lot of losing over the last 70 or 80 years.”

In the long run, he said, cities along the Great Lakes might be enviously referred to as “the Water Belt”—rather than the Rust Belt or the Snow Belt—because “we are sitting on one-fifth of the world’s supply of fresh water.” With a warming climate, their location could become a strategic plus. But in recent memory, factories had still been closing, and populations falling.

“There are communities and individuals our economy has overlooked,” he said. “People whose economic future is uncertain, they can be put on a path to better themselves and their families, with marketable skills that have real value.” As the mayor himself admitted, any sentiments of this sort sound platitudinous. But the problem he’s describing is very obviously real. And the elements of the response—businesses with an intentional civic focus, partnerships among a variety of groups, guiding focus on inclusion—have proven their value in communities with problems more acute than Toledo’s.

“I don’t know what people on ‘the coasts’ might say about towns like Toledo,” the mayor remarked, when I told him I was calling from my house in Washington. “We’re not New York City, and we don’t want to be New York City. You can get anywhere you want, in 12 minutes. If you pay $200,000 for a house, you can get 3,000 square feet.”

He stopped himself, and laughed—“Yes, this sounds like a mayor being a booster. But I think it’s the case for Toledo, and a lot of towns like this, that we have a little bit of a chip on our shoulder. We get the sense that people might be snickering at us. And we make that an advantage, in the civic zeitgeist. It’s a nice town, we get along, and if someone ‘in the family’ gets picked on, everyone stands up for them.”

The chip on the shoulder, very much the spirit of Fresno—or Erie, or Dayton, or San Bernardino, or many other places we have written about—is part of what the Bitwise founders recognized, and welcomed.

“Toledo has been knocked down and punched in the gut several time,” the mayor said. “But I will say that if there is anything about being knocked down, it’s that you know how to get up. Toledo is a resilient place. We know how to take a punch. Toledo is a place that never gives up.”

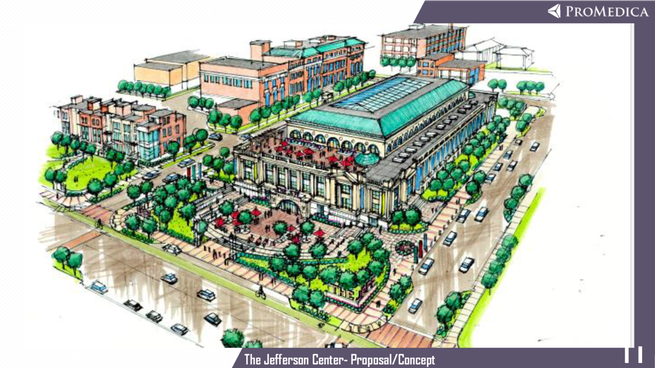

The Jefferson Center: “The property they’re using is an interesting representative of Toledo as a whole,” Nolan Rosenkrans, of the Toledo Blade, told me on the phone this week. He was talking about the vintage-1911 Main Post Office, recently known as the Jefferson Center, which will be the Bitwise/ProMedica site.

“It’s right next to the Toledo Club, another stately historic structure, which is a center of wealth. And on the other side is a homeless shelter and community kitchen. In between is this huge block-long center that’s just empty now, and which is not the easiest kind of structure to redevelop.” He said that he thought most people would be glad the building would survive.

As for the larger success of the project, people in Toledo and elsewhere will have to wait and see. But Bitwise intends this as the first of a series of projects for underdog cities in the Midwest and elsewhere. They will represent important new venues for the drama of whether the American economy can open more possibilities to more of its people.