Join getAbstract to access the summary!

Join getAbstract to access the summary!

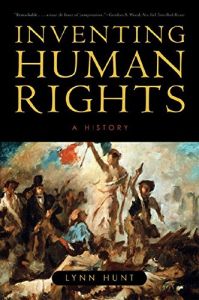

Lynn Hunt

Inventing Human Rights

A History

W.W. Norton, 2008

What's inside?

We take them for granted today, but human rights took centuries to evolve.

Recommendation

Most Westerners take for granted the notion that all men and women are created equal, that political liberties and religious freedom are basic rights endowed by birth, not by class, color or creed. But 250 years ago, even advanced civilizations had no notion of individual rights, according to this intriguing study by Lynn Hunt. The historian vividly describes a time when torture and public execution were commonplace – in the annals of cruel and unusual punishment, the guillotine marked a major improvement – and voting was a rare privilege. Hunt lauds the revolutionaries of France and the American colonies for creating a new framework for equality. Alas, she reports, it took decades before the rights they championed were extended to black and Jewish men or to women of any race or religion. Though narrowly focused on the United States and Western Europe, Hunt’s readable and well-organized book offers a lucid and insightful account of the slow evolution of human rights.

Summary

About the Author

Lynn Hunt is a distinguished research professor at UCLA, former president of the American Historical Association and author of Telling the Truth About History.

Comment on this summary