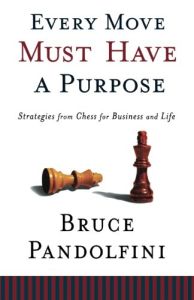

Recommendation

This slim volume, which draws life and business lessons from the game of chess, is one of the better self-help and self-improvement books you’re likely to pick up. At only 115 pages, double-spaced, and a mere 20,000 words, the entire book is about the length of a chapter in most other books in its category. Author Bruce Pandolfini includes just enough chess lore to keep the book relevant to chess, but not so much as to overwhelm a chess-averse reader. He writes concisely, as a chess player plays, with a great deal of concentration and quick, quiet decisions expressed in single sentences. The book offers several fine aphorisms, the sort you will remember long after you have put it down. But it’s not the kind of book you will want to put down. Fortunately, getAbstract is glad to note, it is small enough to fit into a purse or computer bag along with everything else you carry.

Summary

About the Author

Bruce Pandolfini is one of today’s most sought-after chess teachers and most widely read chess writers. He is a regular columnist for Chess Life and was PBS analyst for the 1972 match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky.

Comment on this summary