Join getAbstract to access the summary!

Join getAbstract to access the summary!

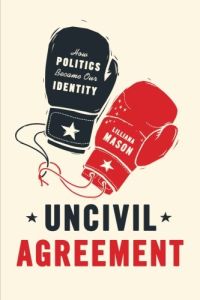

Lilliana Mason

Uncivil Agreement

How Politics Became Our Identity

University of Chicago Press, 2018

What's inside?

Americans may be social animals, but they don’t have to act like political sheep.

Recommendation

In an ideal representational democracy, voters assess policies and align themselves with whichever party best represents their interests. That allegiance can change if the party’s policy changes. But, according to social psychologist Lilliana Mason, policy is becoming less important in American politics than social identity and the desire to “win” – as evidenced by Donald Trump’s success in the 2016 presidential election. Mason argues that, today, Americans’ political identities are strongly tied to their social identities, such as race or religion; and political parties have made such identities core elements of their platforms. The more social connections a person has to their party, the more emotionally invested they are in its success. The resulting social polarization divides American society along partisan lines, heightens intolerance and imperils democracy. Mason explains that a healthy democracy depends on cooperation and compromise; it is dysfunctional when the parties choose victory at any cost over the common good. Extensively researched and refreshingly unbiased, with statistical data to support her findings, Mason predicts that social polarization will increase as long as the two-party system encourages blind party loyalty over policy.

Summary

About the Author

Lilliana Mason is an assistant professor of government and politics at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, the Washington Post, and on NPR.

Comment on this summary