Recommendation

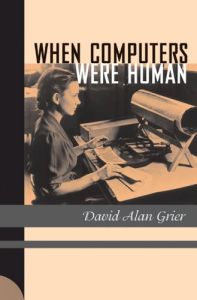

Usually, the word “computer” generates images of a powerful, programmable machine that can perform almost any task. However, a “computer” was originally a person who performed complex math. Some “human computers” were scientists who did advanced calculations, but most were workers who labored over the same types of adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing hour after hour, day after day. Scientist David Alan Grier weaves a wonderful story of the history of computing, framed by the discovery of Halley’s Comet and its three subsequent appearances. The comet gives the story a nice structure that helps readers see the advances in computing over the past three centuries. Grier introduces colorful personalities and covers pivotal historical events in the rise of mechanical computing. getAbstract finds that this history book informs your understanding of how computerization advanced while also being a terrific read.

Summary

About the Author

David Alan Grier is an associate science and technology professor at George Washington University. He has previously published several articles on the history of science and he edits an engineering journal on the history of computing.

Comment on this summary