Henry Fountain, Kendra Pierre-Louis, Hiroko Tabuchi, Brad Plumer, Lisa Friedman, Christopher Flavelle and Somini Sengupta

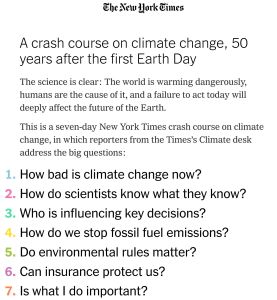

A Crash Course on Climate Change

50 years after the first Earth Day

The New York Times, 2020

What's inside?

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by climate change, here’s what you need to know in a nutshell.

Recommendation

Wondering how big the problem of global warming is, say, compared to the novel coronavirus? Wonder no more. This compelling summary of climate science and policy makes it clear that the world is currently on a path to catastrophe, but quick and strategic changes can minimize harm. From making personal choices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions to supporting policies that incentivize emissions-curtailing societal changes, seven concise, though somewhat scattershot, Q&As make it clear what people can – and must – do to head off an environmental and economic crisis of pandemic proportions.

Take-Aways

- Climate change is happening and it’s a serious problem.

- Scientists learn about climate change through direct observation and clues from the past.

- In the United States, regulations – and those who influence them – are steering the response.

- Revamping the energy and food systems could dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- US climate policy is mired in politics.

- Insurance can protect individuals, but controlling costs can incentivize living in harm’s way.

- Individual and collective actions both matter if people want to stave off disaster.

Summary

Climate change is happening and it’s a serious problem.

As concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases increase in the atmosphere, Earth’s climate is changing, creating a cascade of disruptions to the planet.

“Global warming is happening, and its effects are being felt around the world. The only real debates are over how fast and how far the climate will change, and what society should do.”

Ocean temperatures are rising. Storms and heat waves are becoming more severe. A warming Arctic is altering the jet stream, creating more extreme weather in temperate latitudes. Melting ice is creating positive feedback loops that cause more ice to melt and altering ocean salinity and circulation patterns. The past decade was the hottest on record.

Scientists learn about climate change through direct observation and clues from the past.

Scientists can learn about climate change from straightforward observation of the rising temperatures in the air and the ocean.

“Scientists can also look back even further to figure out temperatures on Earth before any humans were alive.”

They can also look at the history of climate recorded in the rings of trees and samples of ice taken from the Arctic. Carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels is slightly different from carbon dioxide produced by living plants and other sources, so scientists know that the increased concentration in the atmosphere is due to humans.

In the United States, regulations – and those who influence them – are steering the response.

In the United States, federal rules guide action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The fossil fuel industry has long tried to block policies to fight global warming through lobbying and political contributions.

“A tax on carbon emissions could give businesses incentive to find fixes.”

The current administration has been working to undo past initiatives aimed at reducing the risk of climate change, including withdrawing participation in international efforts and upending regulations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In recent years, fossil fuel interests have been initiating some efforts to counter global warming, but there are concerns that the coronavirus pandemic could change the course of these efforts.

Revamping the energy and food systems could dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

To reduce the threat of catastrophe due to global warming will require curtailing the production of greenhouse gases. This will involve four key actions. The first is to kick in solar, wind and other technologies to generate electricity without producing greenhouse gases. The second is to move from fossil fuels to electricity as the source of energy to fuel human enterprise and to reduce energy use where possible.

“As our power plants get greener, the next step is to rejigger big chunks of our economy to run on clean electricity instead of burning fossil fuels.”

The third is to develop new technologies for enterprises that aren’t easily electrified, such as flying airplanes and producing industrial heat. The fourth is to reduce emissions from changes in land use and agriculture through efforts such as reducing deforestation, altering farming and food consumption, and reducing food waste. A tax on carbon emissions, government spending, international cooperation, and help for workers whose jobs disappear in the transition could all contribute to the cause.

US climate policy is mired in politics.

Climate has become a partisan issue in the United States. For the past decade, policy has largely been directed by the president rather than Congress. The Obama administration instituted a number of measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Trump administration has worked to remove many initiatives that combat climate change. Joseph Biden, who is running for president, has proposed working to reduce emissions. Congress is largely at an impasse.

Insurance can protect individuals, but controlling costs can incentivize living in harm’s way.

Some people want to rely on insurance to protect themselves from flooding, wildfires and other adverse impacts of climate change. One approach is to let insurance reflect the cost of the harm. But lawmakers are blocking this to keep insurance affordable and prevent the collapse of local economies, and are instead subsidizing insurance. This removes a disincentive to living in areas at high risk of flood and fire.

Individual and collective actions both matter if people want to stave off disaster.

To avoid catastrophe, humans need to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half in the next 10 years. The choices individuals, particularly in rich countries, make matter – not only for their isolated impact, but also for the snowball effect they can have in inspiring others to conserve resources and use renewable energy.

“The future isn’t set in stone. There are many futures possible, ranging from quite bad to really catastrophic. Which one plays out is up to us to decide.”

“Present bias” causes people to prefer current to future well-being, so government needs to help nudge behavior through policies like carbon prices. It’s not too late to change course and avoid catastrophe.

About the Authors

Henry Fountain, Kendra Pierre-Louis, Hiroko Tabuchi, Brad Plumer, Lisa Friedman, Christopher Flavelle and Somini Sengupta are reporters for The New York Times climate desk.

This document is restricted to personal use only.

My Highlights

Did you like this summary?

Read the articleThis summary has been shared with you by getAbstract.

We find, rate and summarize relevant knowledge to help people make better decisions in business and in their private lives.

Already a customer? Log in here.

Comment on this summary